‚Need Love‘

by Miriam Zlobinski

Love, as often sung about as wept over, seems to be a primal force. There are few people who do not seek it, and many different ideas about its modalities. A quote in the exhibition expresses the desire “Need Love.” Love is demanded; a need that one can relate to – who doesn’t long for it? The socially constructed image of relationships plays on romantic notions of longing for intimacy, comfort and lust. The pursuit of these feelings and the loneliness without a “better half” are producing its own blossoms all over the world.

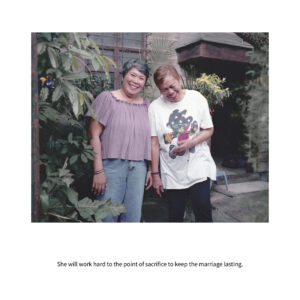

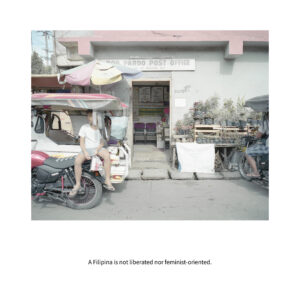

In her project “The Many Wives of Mr. _” Sina Niemeyer gives a differentiated insight view into the business of arranged marriages, a supermarket of love full of women. Based on found letters from Filipinas willing to get married to a Berlin bachelor from the 1980s, Niemeyer set out to find the senders. The private documents and compiled interviews provide a multi-faceted, personal understanding of the realities of women’s lives as they offer themselves on the international marriage market.

Love as a transaction has a long history and even became an important economic factor for the press throughout Europe in the 18th century. With the creation of marriage advertisements in the classified ads, circulations increased and a business grew in virtue of the desires, needs and demands regarding potential spouses. Love, in a romantic sense, still presents itself today as a haunting promise between the lines in every ad, in every letter or video by dating agencies. However, the institution of marriage is much more than a promise between two people. If one follows the formulated needs, marriage as an individual space of longing is based on concrete demands on appearance and characteristics such as loyalty and wealth. Without money, there is no ring, no dowry, no lavish party for the “most beautiful day in life.” Harmony, contentment, bliss – the promises of marriage agencies – become romantic ornaments alongside legal facts. Spouses become financially responsible for each other, instead of the state. For a long time, the mere opportunity of getting married also legitimized heteronormative life models in distinction to devalued behavior such as having sex or children without being married.

At the time when the letters were making their way to their recipient Mr. _, journalistic reports of sexual exploitation of Asian women were on the rise in the early 1980s. Despite the situation being denounced, so-called sex tourism and the mail-order bride market simultaneously popularized a stereotype of available as well as dependent women.

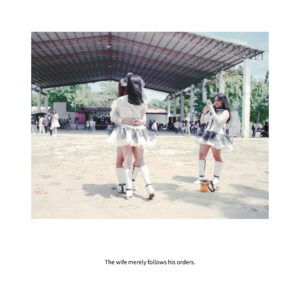

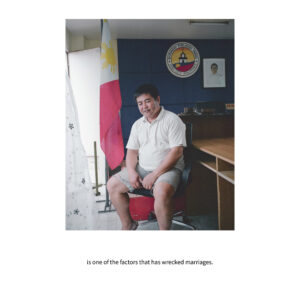

Sina Niemeyer experienced this world up close by participating in an organized singles tour. The organized marriage business contributes a substantial amount to intercultural marriage migration, meaning marriages in which one partner leaves their country and culture behind to move to another country. Generally, this form of marriage is described by an exchange on an equal footing, a cultural dialogue. In the case of Filipinas, asymmetrical power relations yield the women to the benevolent behavior of the marriage candidates. The women, however, are not guided by a sense of loneliness, but by the even culturally inherited perspective of acquiring a better life, away from poverty, that often leaves no alternative. The relentless objectification of the women is revealed precisely in the advertising promises of the marriage agencies.

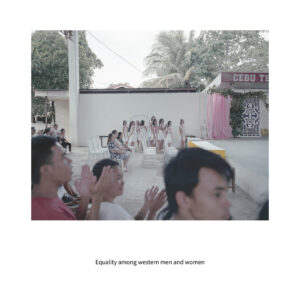

The program, the journey and the dating procedures are tailored to the paying men from the USA or Europe. The agencies’ advertising videos promote the objective of a perfect romance in which the young women, each one of them tagged with a clearly visible number, present parade in tiny little dresses in front of the seated older men. In the assembled material, though, the subject-object relationship becomes visually palpable once again. The men are pixelated for privacy, the women are not. The market uses the narrative of a partnership and at the same time serves the desire of a strong disparagement of the potential spouses. Nonetheless, Filipinas and their families build on a future with an unknown man.

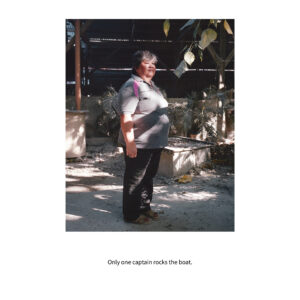

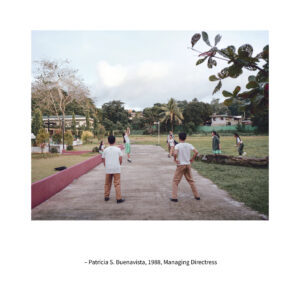

Other men seem naive or even pushed by their parents to finally find a wife. In small gestures and moments, Niemeyer explores the feelings behind their intentions, the microcosm of love. She finds objects, takes her time for intense portraits. At the same time, she reveals attitudes of entitlement by making her protagonists reflect on questions such as: What do I think I deserve and what kind of promises can I request from someone?

The promise of a better life is so tempting that Filipinas often pay for their passports and visas themselves. Some agencies even oblige the women to pay for the costs if no marriage takes place. Apart from agencies, it is often relatives or couples already living abroad who are involved in matchmaking. Unfortunately, there are no official figures on marriage agencies operating in the Philippines. The commercialization of love and the marital ritual itself sustains the business, as does the never-ending stream of potential brides.

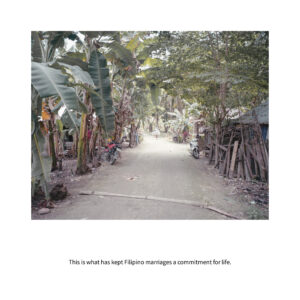

The high numbers of emigration, including the strong general labor migration from the Philippines, is closely linked to global dynamics based on post and neocolonialist structures, global capitalism, and hegemonic sense of entitlement. Even former marriage candidates become marriage brokers themselves. The Philippines live off the export of human labor. The economy and society cannot be understood without this phenomenon. Family income is derived from absent family members. The number of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW), as this group is officially called, is highly impressive. 13 million people – nearly 10 percent of the population and just over one-fifth of the labor force – were resident in over 100 countries outside the Philippines at the end of 2015. An estimated 5,000 people leave the country every day to take up jobs overseas.

In 1975, only 12 percent of Filipino migrant workers were women, but by 2002 their share had risen to 69 percent. The feminization of labor migration is due to the demand for “female” skills. In particular, there is a demand for cleaners, service staff in the catering sector and, of course, domestic helpers – for Qatar, Oman, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore and even for Romania in faraway Europe. In addition, women in the Philippines bear a special and also financial responsibility with regard to the family. According to Philippine sociologist Belinda Medina, they show greater commitment to those back home and transfer a much larger proportion of the money they earn.

“Need Love” is associated with a demand for love. Behind this idea, just as with marriage and labor migration, lie promises. The damage resulting from these promises, however, is never at the expense of the structure; it affects the individual and, in the case of the Philippines, often an individual woman.