‚Painfully Covered by Years of Dust and Nevertheless Unforgotten: Für Mich — A Way of Reconciliation‘

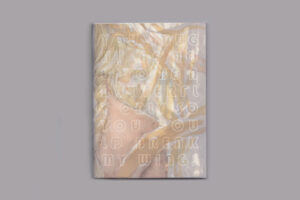

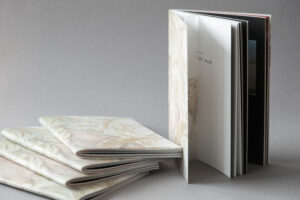

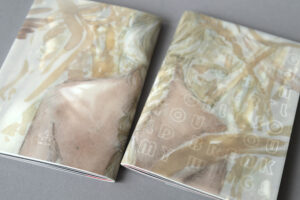

Für Mich—A Way of Reconciliation by Sina Niemeyer comes across like the diary of a fighter. It takes the artistic form of a psychogram, consisting of the photobook You Taught Me How to Be a Butterfly Only So You Could Break My Wings and the video Goodbye. In her works the photographer offers deep insight into the inner life of a “survivor” of the sexual violence she had experienced as a child. By collaging the stylistic convention of family albums with that of photographic still lives and mixing documentary and more abstract images in her film, the viewers remain uncertain whether they are viewing fiction by Niemeyer or her autobiography. The film and photo album yield a body of work that oscillates between the meticulous gathering of evidence and therapeutic processing.

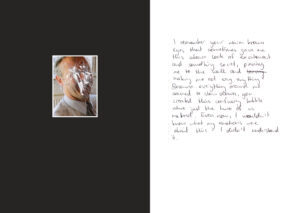

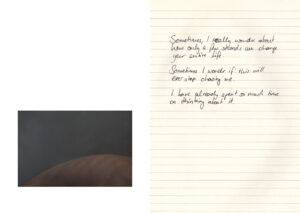

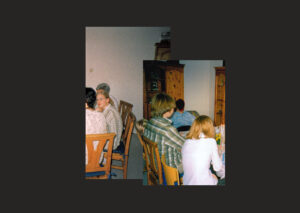

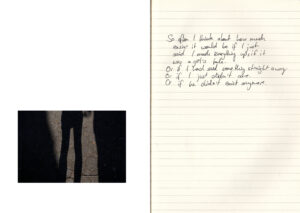

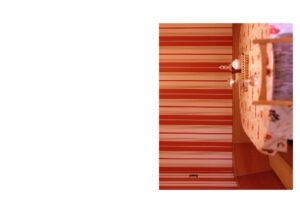

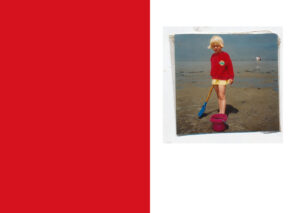

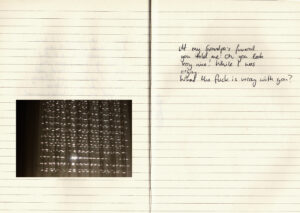

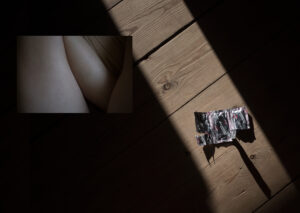

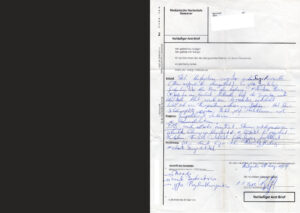

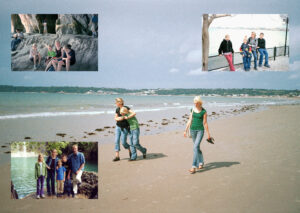

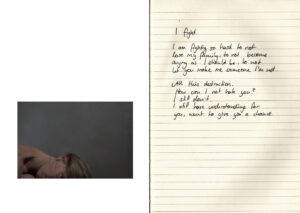

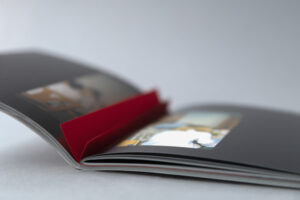

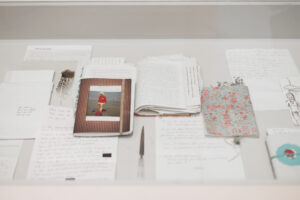

The video initially appears to be a series of chance images that gradually take on the form of a metaphorical collage. The soundtrack is no less confusing: is it a conversation between victim and perpetrator? The dialogue is reminiscent of an interrogation, in which not guilt or innocence are negotiated, but instead the desire to understand the past takes center stage. The photo album takes an intimate look at this past: written notes, partially destroyed photos from a family album, self-portraits, and situational images that look like still lives. Together the book and the film present the assessing and processing of the experience of sexual violence in childhood from the victim’s perspective.

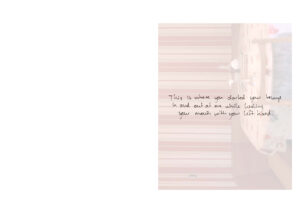

The photo book is filled with fragments of male portraits (presumably of the perpetrator), whose face and heart have been cut out, scratched, or collaged. By destroying the face, different logics of (in) visibility collide: the pictures are evidence of rampant emotions, of pain, anger, and deep emotional wounds that were left behind by the culprit’s actions. Simultaneously the perpetrator’s identity is given a certain amount of protection. In this context the written comments can also be interpreted as an attempt at rationalization. They express not only their own feelings in words, but also even show understanding for the perpetrator.

The Video

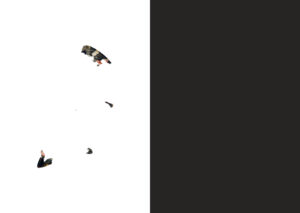

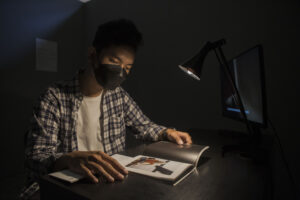

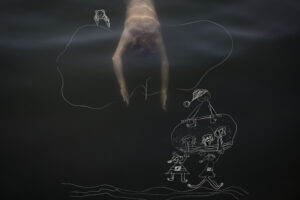

The images in the video cannot be initially reconciled with their content without the help of the soundtrack. The beeping of a heartlung machine becomes the pulse beat of the work. It is transferred to the viewers, pulling them in and making them a part of the horrible experience. This also reveals the fine line between voyeurism and participation on which the viewers are fascinated and simultaneously appalled by the story. The shot of a beetle struggling on its back becomes a symbol for the interview fragments with the perpetrator. His words of denial, the lame attempt at an explanation, and his defense become proof of his own weaknesses. He becomes a pitiful creature who – similar to the wriggling beetle – dodges the aggressive questions. Beetles, flies, spiders, and butterflies pervade Niemeyer’s work. They symbolize attacks, fears, and threats. An agitated swarm of moths and flies flutter in the light of a bright light, illuminating a past that – covered by the dust of the years would rather be forgotten – but must not and cannot be forgotten. The compulsion to remember and the inability to forget clash with the aversion to remember and compulsion to suppress. This fragmentation of memory is also reflected in the aesthetics of the photographs and images.

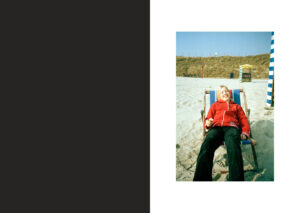

While the book presents destructive power and emotions, the video serves to purify the emotions, particularly toward the end. The doctor’s letter between the pictures in the photobook mark a caesura that is resumed in the video – the scenery changes following the sustained pure tone. The nature shots that cloak the protagonist’s poetic monologue in the final third of the film are transformed into symbols of spiritual healing and surpassing the perpetrator and the trauma.

The Book

Sexual abuse of children and adolescents is a problem all over the world. According to the World Health Organization of the United Nations (WHO), eighteen million minors are affected in Europe – plus a large number of unknown cases. According to a study on sexual abuse of children that was initiated by the German government in 2017, one out of eight children is affected. Half of the perpetrators are close family members or friends. In 2016 there were twelve thousand investigations and criminal proceedings, of which 70 percent were female victims and 25 percent were male.

By bringing attention to her own family pictures, Niemeyer poses the painful question in her direct environment of “why didn’t you notice anything?” and confronts viewers with this question as a sort of admonition and warning. In this way the work connects the child victim and the young woman who is looking back at her memories and has the courage to confront the perpetrator. Sina Niemeyer’s A Way of Reconciliation is thus a manifestation of strength and also symbol as an incentive and monument of hope for the countless silent victims of such abuse.

by Mara-Elena Zöller, Alina Valjent & Stefan Becht